HPV Vaccination After 26 Years of Age Found Less Cost-Effective

The journal PLOS published a cost-effectiveness analysis that evaluated extending human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccinations to ages 30, 35, 40, or 45.

This peer-reviewed study found HPV vaccination of women and men aged 30 to 45 years provides limited health benefits at the population level, at a substantial cost.

The HPV vaccine price was the primary cost.

This study found that HPV vaccination to older ages was inefficient or associated with unfavorable Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio (CER) in the USA.

Furthermore, the sensitivity analysis revealed that assumptions about cervical screening compliance, vaccine costs, and the natural history of noncervical HPV-related cancers could significantly impact the vaccination strategies’ estimated cost-effectiveness.

However, even with the most extreme assumptions, both models almost universally found that the cost-effectiveness of HPV vaccination for adults aged 30 to 45 years was more significant than $200,000 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY).

The only exception was in the scenario assuming imperfect screening compliance. One model found that vaccinating up to ages 40 and possibly 45 years could be cost-effective if assuming an upper-bound willingness-to-pay threshold of $200,000 per QALY.

These international researchers stated, ‘cervical screening is a very effective mechanism for secondary prevention, with the absolute effectiveness increasing, particularly in women over the age of 25 to 30 years.’

‘In general terms, the impact of secondary prevention of cervical cancer is critical to incorporate, and the CISNET models were able to achieve this in great detail.’

Moreover, this analysis has several limitations. Where possible, the researchers erred in the direction of making assumptions that were favorable to increasing the age of vaccination, including assuming no delay between the reduction in HPV infections from vaccination and the reduction in genital warts.

There are approximately 100 types of HPV that have been identified, at least 40 of which can infect the genital area, says the U.S. CDC.

The Gardasil 9 vaccine produced by Merck consists of HPV proteins, Types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58.

HPV infections can lead to certain cancers. Many females with cervical cancer were probably exposed to cancer-causing HPV types in their teens and early 20s. Unlike some other cancers, cervical cancer is not thought to be passed down through family genes.

Additionally, males can get HPV, causing anal and throat cancers and genital warts say the CDC. Most HPV infections are self-limited and are asymptomatic or unrecognized. Most sexually active persons become infected with HPV at least once in their lifetime.

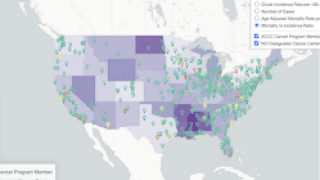

Although the HPV vaccine holds promise to nearly eliminating cervical cancer with complete population coverage, U.S. vaccination rates remain far below those in other high-income countries.

A Research Brief published by the American Academy of Pediatrics in February 2021 reported the proportion of up-to-date adolescents has improved over time.

However, in 2017–2018, 7.3 million vaccine-eligible US adolescents were unvaccinated.

Notably, despite a provider recommendation, the parents of 60.6% of unvaccinated adolescents had no intention to initiate the HPV vaccine series.

This new study was conducted to directly inform the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ deliberations to guide HPV vaccination policy for women and men in the United States.

These researchers received grant support from the U.S. National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (grant number U01CA199334). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. All other authors declare no conflicts.

PrecisionVaccinations publishes research-based vaccine news.

Note: updated with additional citation.

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee