Insulin-Producing Organoids Considered Potential Type 1 Diabetes Treatment

For millions of Americans with type 1 diabetes, their immune system destroys insulin-producing beta cells of the pancreas that control the amount of glucose in the bloodstream.

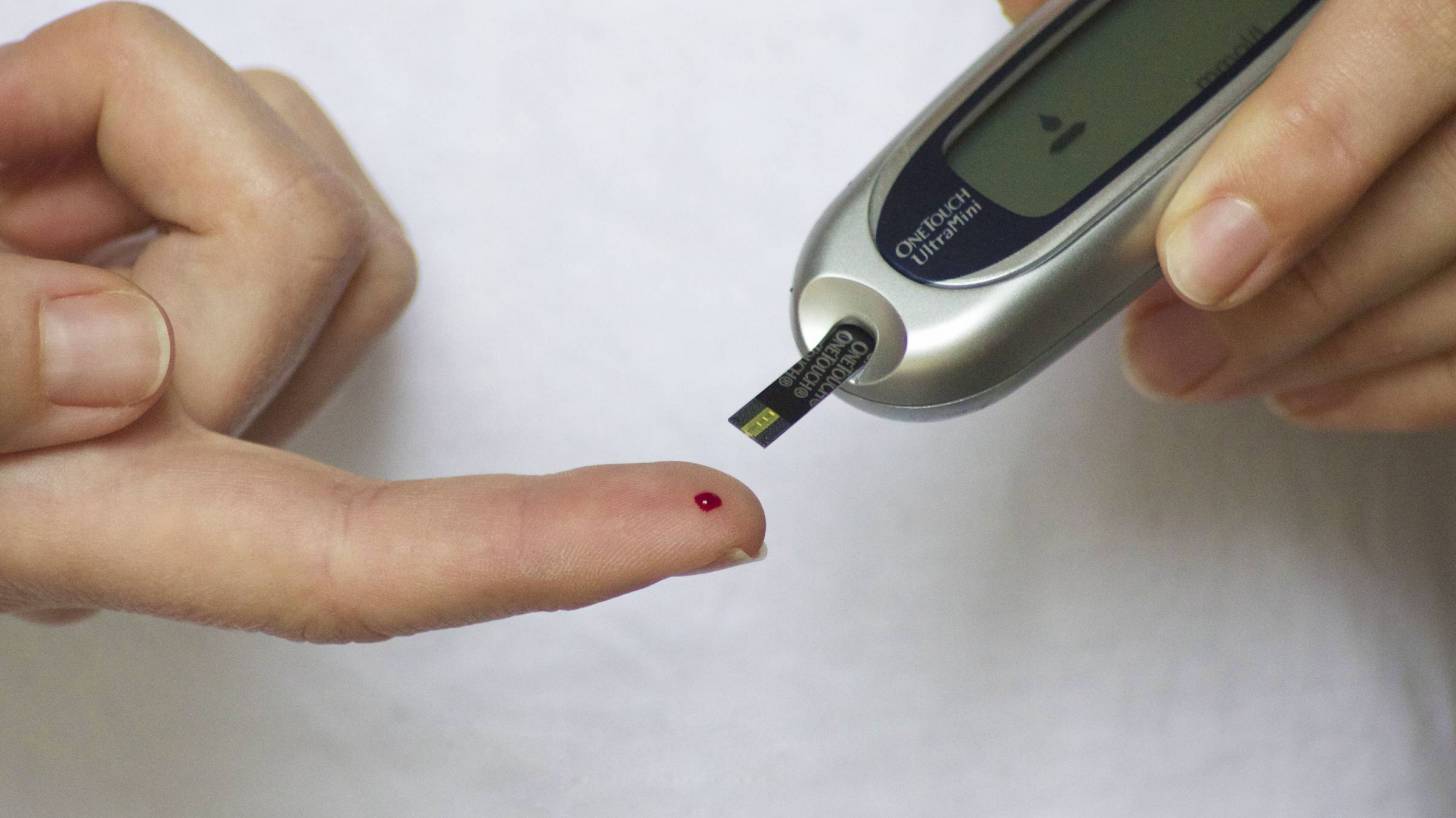

‘As a result, these individuals must monitor their blood glucose often and take replacement doses of insulin to keep it under control,’ stated Dr. Francis S. Collins, in his September 25, 2020, National Institutes of Health (NIH) Directors blog.

‘Such constant attention, combined with a strict diet to control sugar intake, is challenging—especially for children,’ continued Dr. Collins.

Additional insights from this week’s blog are inserted below.

‘For some people with type 1 diabetes, there is another option. They can be treated—maybe even cured—with a pancreatic islet cell transplant from an organ donor.

These transplanted islet cells, which harbor the needed beta cells, can increase insulin production. But there’s a big catch: there aren’t nearly enough organs to go around, and people who receive a transplant must take lifelong medications to keep their immune system from rejecting the donated organ.

Now, NIH-funded scientists, led by Ronald Evans of the Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA, have devised a possible workaround: human islet-like organoids (HILOs). These tiny replicas of pancreatic tissue are created in the laboratory.

Remarkably, some of these HILOs have been outfitted with a Harry Potter-esque invisibility cloak to enable them to evade immune attack when transplanted into mice.

Over several years, Doug Melton’s lab at Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, has worked steadily to coax induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, which are made from adult skin or blood cells, to form miniature islet-like cells in a lab dish.

My own lab at NIH has also been seeing steady progress in this effort, working with collaborators at the New York Stem Cell Foundation.

Although several years ago researchers could get beta cells to make insulin, they wouldn’t secrete the hormone efficiently when transplanted into a living mouse. About four years ago, the Evans lab found a possible solution by uncovering a genetic switch called ERR-gamma that when flipped, powered up the engineered beta cells to respond continuously to glucose and release insulin.

In the latest study, Evans and his team developed a method to program HILOs in the lab to resemble actual islets. They did it by growing the insulin-producing cells alongside each other in a gelatinous, three-dimensional chamber.

There, the cells combined to form organoid structures resembling the shape and contour of the islet cells seen in an actual 3D human pancreas. After they are switched on with a special recipe of growth factors and hormones, these activated HILOs secrete insulin when exposed to glucose.

When transplanted into a living mouse, this process appears to operate just like human beta cells work inside a human pancreas.

Another major advance was the invisibility cloak.

The Salk team borrowed the idea from cancer immunotherapy and a type of drug called a checkpoint inhibitor. These drugs harness the body’s own immune T cells to attack cancer.

They start with the recognition that T cells display a protein on their surface called PD-1. When T cells interact with other cells in the body, PD-1 binds to a protein on the surface of those cells called PD-L1. This protein tells the T cells not to attack.

Checkpoint inhibitors work by blocking the interaction of PD-1 and PD-L1, freeing up immune cells to fight cancer.

Reversing this logic for the pancreas, the Salk team engineered HILOs to express PD-L1 on their surface as a sign to the immune system not to attack.

The researchers then transplanted these HILOs into diabetic mice that received no immunosuppressive drugs, as would normally be the case to prevent rejection of these human cells. Not only did the transplanted HILOs produce insulin in response to glucose spikes, but they also spurred no immune response.

So far, HILOs transplants have been used to treat diabetes for more than 50 days in diabetic mice. More research will be needed to see whether the organoids can function for even longer periods of time.

Still, this is exciting news and provides an excellent example of how advances in one area of science can provide new possibilities for others. In this case, these insights provide fresh hope for a day when children and adults with type 1 diabetes can live long, healthy lives without the need for frequent insulin injections,’ concluded Dr. Collins blog.

Dr. Collins was appointed the 16th Director of the NIH on August 17, 2009. In this role, Dr. Collins oversees the work of the largest supporter of biomedical research in the world, spanning the spectrum from basic to clinical research.

PrecisionVaccinations publishes research-based news.

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee