Can the Americas Beat Malaria?

The Americas have made great strides in the fight against malaria. But, in countries like Venezuela, malaria cases are increasing.

On November 6, 2019, ‘Malaria Day in the Americas’ is being observed for the 13th time. It is envisioned to be the platform upon which countries of the Region can engage in a year-round campaign to combat the disease.

The Americas Region is adapting the theme “Zero malaria starts with me”.

According to the article Nothing But Nets, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) region is at a critical crossroads.

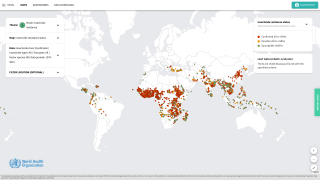

The countries of the Americas are committed to eliminating malaria from the region. The goal is ambitious, as an estimated 132 million people are currently at risk of malaria transmission.

Mosquitoes carrying the deadly malaria parasite have flown along next to humans for thousands of years, and the disease appears in documented reports as early as 2700 B.C.

The good news is…. Recent prevention efforts are working.

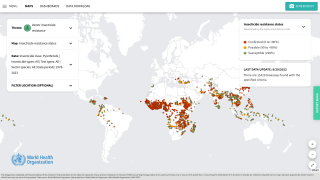

Since 2000, vector control, improved diagnosis, and the introduction of new, first-line malaria treatment have helped avert an estimated 7.2 million cases and 3,000 deaths, reports the PAHO.

In 2018, Paraguay became the first country in the Americas to be granted malaria-free status by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 45 years.

Followed by Argentina in 2019.

This WHO status means both countries have demonstrated they have the capacity to prevent the re-establishment of malaria transmission.

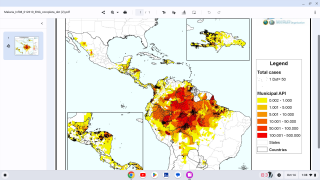

Despite these impressive advances, malaria has again risen in the region, with 764,000 cases estimated per year in 2018, compared to 389,390 in 2014.

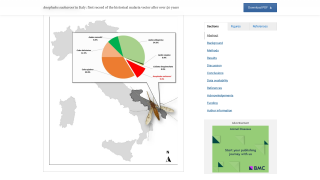

The crisis in Venezuela accounts for much of this increase.

In one year, from 2016 to 2017, Venezuela saw more than a 170 percent increase in reported cases and now accounts for 53 percent of all known cases in the PAHO region.

Malaria affects the most vulnerable populations, particularly people who live in isolated and rural communities, lack access to adequate health care, face cultural and linguistic barriers, and experience marginalization.

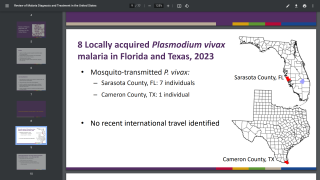

Malaria is caused by the parasite Plasmodium, a single-celled organism that has multiple life stages and requires more than one host for its survival. Five species of the parasite cause disease in humans – Plasmodium falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae, and P. knowlelsi.

Plasmodium falciparum is the most dangerous strain in humans and the target of most scientific research today.

On September 11, 2019, a report published by The Lancet, said ‘a future free of malaria can be achieved as early as 2050.’ The Lancet report’s authors proposed 3 ways to speed up malaria’s decline.

- Existing malaria-fighting tools such as bed-nets, medicines, and insecticides should be used more smartly

- New tools such as vaccines should be developed

- Governments in both malaria-affected and malaria-free countries need to boost investment by about $2 billion a year to accelerate progress

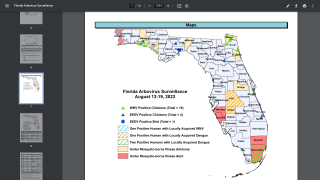

In the USA, millions of residents travel to countries where malaria is present. About 1,700 cases of malaria are diagnosed in the United States annually, mostly in returned travelers, says the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Travelers who become ill with a fever or flu-like illness either while traveling in a malaria-risk area or after returning home for up to 1 year should seek immediate medical attention and should tell the physician their travel history.

- Mosquirix Malaria Vaccine Effectiveness Measured By Antibody Quantity and Quality

- Can Malaria Vaccine Mosquirix Save More Children?

Travelers who are assessed at being at high risk of developing malaria while traveling should consider carrying a full treatment course of malaria medicines with them.

Depending on the medicine they are using for prevention, this could either be atovaquone/proguanil or artemether/lumefantrine, said the CDC in August 2019.

Although progress has been made in vaccine science, there is currently no licensed malaria vaccine on the market in the USA.

The complicated life cycle of Plasmodium presents a challenge to malaria vaccine development. Researchers must determine which life stage of the parasite to target, or whether the vaccine needs to combine elements that target more than one life stage.

However, recent findings allow us to be optimistic about the possibility of an effective malaria vaccine.

As an example, GSK’s RTS,S, known as Mosquirix, has completed Phase III clinical testing and Mosquirix has been approved for large-scale pilot studies.

The Mosquirix vaccine candidate is designed to prevent the parasite from infecting the liver, where it can mature, multiply, re-enter the bloodstream, and infect red blood cells, which can lead to disease symptoms.

And, a transmission-blocking vaccine candidate is the Pfs25-EPA which is being developed by the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Laboratory of Malaria Immunology and Virology and Johns Hopkins University Center for Vaccine Research.

The idea behind this vaccine is that if the body can develop antibodies against the Pfs25 antigen, a mosquito taking a blood meal will take up some of these antibodies into its stomach. There the antibodies will encounter the antigen, enabling them to interfere with development and kill the parasite.

The CDC says any vaccine can cause side effects, which should be reported to a healthcare provider asap.

A world free of malaria would offer enormous benefits in terms of health and equity, concluded the Nothing But Nets article, written with Judith Recht Ph.D.

Nothing But Nets is the world’s largest grassroots campaign to fight malaria. Together with UN partners, Nothing But Nets raises awareness, funds, and voices to send life-saving bed nets to protect families from malaria.

Malaria news published by Vax Before Travel

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee