West Nile Fever Needs A Vaccine

The search for vaccines against the West Nile virus is one of the major challenges of global epidemiology.

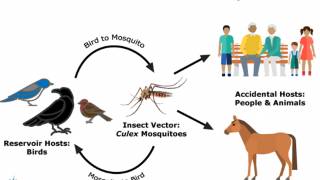

New pathological agents continue to emerge, such as the arbovirus transmitted by mosquitoes that cause West Nile fever.

West Nile fever affects thousands of people each year and is asymptomatic in 80 percent of cases.

Roughly 20 percent of infected people develop fever and other symptoms.

But, in fewer than 1 percent of cases, West Nile fever affects the central nervous system, causing meningitis, encephalitis, and in extreme cases, an acute paralysis that leads to death.

As yet, there are no vaccines against the virus.

A new study by Dr. Paulo Zanotto head of the Molecular Evolution & Bioinformatics Laboratory (LEMB) at the University of São Paulo's Biomedical Science Institute (ICB-USP) in Brazil, found that: the relatively mild lineage 8 strains could theoretically "teach" the immune system to defend the organism against all lineages, especially the more widespread lineages 1 and 2, as well as 7, the most virulent.

"With the exception of a single possible accidental infestation, which occurred in vitro in Africa, lineage 7 has never been isolated in humans."

"But it was devastatingly lethal to mice in laboratory tests," Dr. Zanotto said.

In this study, three novel genes isolated from samples of the virus collected in West Africa by Di Paola and Fall were sequenced. The genes in question were representative of the most globally widespread lineage (1), the most virulent (7), and the least virulent (8).

Once sequenced, the genes were compared with the 862 West Nile virus gene sequences available from GenBank. Of these, 770 were lineage 1a from the Americas.

To reduce computer processing requirements, all lineage 1a sequences were removed, except for a single representative sequence. The researchers ended up with 95 sequences for phylogenetic analysis. The results included the discovery of two important traits of lineages 7 and 8.

In the case of lineage 8 (the least virulent), they detected substitution of the gene P122S, which induces mutations that may be linked to the lineage's low replication rate and could, therefore, explain its low virulence.

"This is why lineage 8 would be ideal for a vaccine," Zanotto said, adding that the development of a vaccine based on a virus with very low virulence would be capable of conferring immunity against the more dangerous lineages 1, 2 and 7 without the risk of producing symptoms of the disease.

In the case of lineage 7, the Brazilian and Senegalese virologists were able to identify a mutation (in gene S653F NS5) that is associated with an increased resistance to interferons, proteins made and released by the immune system's white blood cells in response to the presence of viruses and other pathogens to interfere with their replication.

This mutation could help explain the high virulence of lineage 7.

The low virulence of lineage 8 and high virulence of lineage 7 were tested, confirmed and measured both in vitro, using infected cells, and in vivo, by inoculating mice in the Dakar laboratory. In the case of lineage 8, the virus displayed a low capacity to replicate in vitro and almost no virulence in mice.

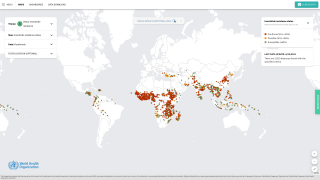

First isolated in the West Nile District of Uganda in 1937, the disease carried by mosquito-infected migratory birds from Africa, the virus was spread through Europe and into Russia.

It reached North America in 1999 and has caused outbreaks in Canada (1999-2007), the United States (1999-2012) and Mexico (2003).

Since then, more than 20,000 cases have been reported in North America, with almost 1,800 deaths.

Paolo Zanotto, Ph.D., said, "How long will it take for migratory birds that spend the summer in North America to bring the virus to their winter refuges in Central America?”

This immune defense strategy is similar to that used by flu vaccines, which combine the most recent strains of the influenza virus to combat the "flu of the year", always caused by an emerging strain to which humans have not developed immunity.

The article is published in PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases and is the result of collaboration among virologists at Institut Pasteur de Dakar in Senegal, the University of São Paulo and the Federal University of São Carlos, São Paulo State, Brazil.

This work has been financially supported by Institut Pasteur de Dakar, and funded by EU grant HEALTH.2010.2.3.3-3-261391 EuroWestNile and the Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa (CNPq) project 441105/2016-5. We also thank the Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) for the funding (project #2013/22136-1 and #2014/17766-9). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

The authors declared that no competing interests exist.

The São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) is a public institution with the mission of supporting scientific research in all fields of knowledge by awarding scholarships, fellowships, and grants to investigators linked with higher education and research institutions in the State of São Paulo, Brazil.

Editor: David W.C. Beasley, University of Texas Medical Branch, United States.

For more information about the research visit São Paulo Research Foundation.

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee