Glioblastoma Vaccine Therapy Study Launched at Rush Hospital

A new clinical trial testing whether an experimental vaccine can help patients' immune systems stop the spread of glioblastoma has launched in Chicago at Rush University Medical Center.

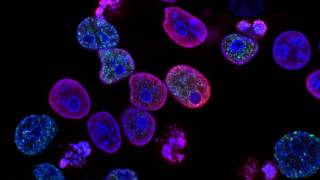

Glioblastomas (also called GBM) are malignant Grade IV tumors, where a large portion of tumor cells are reproducing and dividing at any given time, says the American Brain Tumor Association.

There is no known cure for glioblastoma tumors, and median survival is just four months without treatment and 15 to 19 months with treatment.

Glioblastoma can be difficult to treat since some cells may respond well to certain therapies, while others may not be affected at all. Because of this, the treatment plan for glioblastoma may combine several approaches.

Led by neuro-oncologist Dr. Clement Pillainayagam, this phase II clinical trial is testing an investigational vaccine that will be given in conjunction with bevacizumab, an FDA-approved drug that targets the proteins glioblastoma cells need to grow blood vessels.

Half of this clinical study’s participants will be treated with bevacizumab plus the experimental vaccine.

The vaccine (DSP-788-201G) is derived from peptides (short chains of amino acids) produced by the WT1 gene that is found in many types of cancer cells, including glioblastomas.

The vaccine is used by the HLA (human leukocyte antigen) system, cell surface proteins that help regulate the immune system.

"While the bevacizumab helps starve the tumor by blocking the formation of blood vessels inside it, we hope the vaccine revs up the immune response by helping the body recognize that these cancer cells are a threat," Dr. Pillainayagam said in a press release.

"Our immune system would typically put a stop to cancer cells growing, but glioblastoma cells suppress this process." Dr. Pillainayagam explained.

"Bevacizumab has been shown to help the immune system starve tumors of their blood supply as well as decrease the immunosuppressed state around the tumor.”

“But, that just isn't enough," Dr. Pillainayagam said.

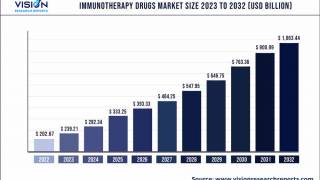

Though the development in recent years of therapies that help people's own immune system target cancer cells has meant new options for many types of cancers, very few immunotherapies for cancers in the brain have shown promise.

"The brain has different types of immune cells that work in unique combinations. Thus, trying to understand how to unleash our own immune systems is a challenge," Dr. Pillainayagam says.

One challenge is actually a barrier: The human body evolved a layer of specialized cells, called the blood-brain barrier, that line the blood vessels in the brain, providing extra security from threats such as viruses and bacteria that circulate in the rest of the bloodstream.

That extra layer of protection also prevents many cancer-fighting drugs from working.

By some estimates, 98 percent of current FDA-approved drugs do not enter the brain because of the blood-brain barrier, said Dr. Pillainayagam.

To be eligible for this clinical trial, patients must meet the following criteria: Have a diagnosis of glioblastoma; Have evidence of recurrence or progression of disease; Have recovered from effects of all prior therapies.

Patients cannot participate if they have received prior bevacizumab therapy, or have received antineoplastic therapy, including radiation therapy, for first relapse or recurrence.

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee