Prepare to Prevent the Next “Disease X”

‘Vaccines are at the heart of how modern societies counter infectious disease threats. They are our most potent tool against pandemic risks and will be critical to any future response,” wrote Dr. Richard Hatchett, CEO of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI).

“The faster an effective vaccine is developed, the faster an incipient pandemic can be contained and controlled.”

Excerpts for Dr. Hatchett’s December 2021 post are inserted below:

“The X in “Disease X” stands for everything we don’t know.

It's a new disease, about which we will know very little when it first emerges: it may or may not be deadly, highly contagious, and a threat to our way of life.

We also don’t know when or how it will come across the viral frontier and infect people.

But we do know that the next Disease X is coming, and we must be ready.

In many ways, the COVID-19 pandemic is ‘proof of concept’ for the prototype-vaccine approach to rapidly developing vaccines against new viral threats.

The aspiration of the CEPI is for the world to be able to respond to the next “Disease X” with a new vaccine in just 100 days.

That’s just three months to defuse the threat of a pathogen to cause a pandemic.

Coupled with improved surveillance providing early detection and warning, and with swift and effective use of non-pharmaceutical interventions, delivering a vaccine in 100 days would give the world a fighting chance to extinguish the existential threat of a future pandemic virus.

Before the SARS-CoV-2 virus emerged, the previous vaccine-development record was for a live attenuated mumps vaccine, which took less than five years.

By comparison, the 326 days it took from the SARS-CoV-2 virus being identified to bring a COVID-19 vaccine into emergency use represented a quantum leap.

With tightening and shortening at each development stage and rethinking how we establish safety and efficacy for emergency response vaccines, cutting that timeline to 100 days is entirely feasible.

Scientifically, it’s about making advances across the whole life cycle of pandemic preparedness—from the moment a new pathogen is identified, through the rapid prototyping of a vaccine candidate, the testing and authorization of that vaccine to get it into the arms of people at risk.

Not all new diseases have pandemic potential.

There are around 260 viruses—belonging to roughly twenty-five viral families—known today to be able to infect humans.

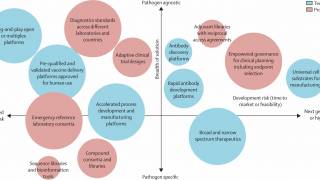

Realistically, we can’t create individual new vaccines against several hundred or more potential or developing threats, let alone the 1.6 million or so more viral species that may exist in mammal or bird hosts and have yet to be discovered, but we can develop vaccines against prototypes of these threats.

In other words, we can focus our efforts on pathogens that exemplify some or all of the worst traits of a particular viral family.

For several years before the emergence of SARS-Cov-2, scientists were already working on vaccines against MERS and SARS, pathogens from the same coronavirus family.

What they learned enabled them to pivot quickly and respond at lightning speed to the new virus, laying the groundwork for the record-breaking effort to develop COVID-19 vaccines.

Scientists have been honing so-called rapid-response platforms to make “plug-and-play” vaccines. Some used mRNA technology, and others, like the University of Oxford’s ChAdOx, used viral vectors.

These innovations empower vaccine makers to ‘plug’ in the genetic code from a novel coronavirus that would trigger a protective immune response.

In this way, when a newly emerging virus comes across the frontier—and that is most certainly a “when” and not an “if”—we’ll have banked a vast amount of data on safety and immunogenicity regarding platform technology and the antigens of viruses that are closely related, if not precisely the same, as the new Disease X.

Creating the vaccine library could mean developing as many as 100 prototype vaccines to ensure we’ve got something in the knowledge bank to help us cover almost any threat.

If there’s one thing we found out during the COVID-19 crisis, it’s that pandemics are devastatingly expensive.

Unfortunately, being correctly prepared doesn’t come cheap.

By the end of 2025, it is forecast that COVID-19 will have cost the world $28 trillion over five years. The human cost is something we will never quantify, but its effects will undoubtedly reverberate for generations.

For its part, CEPI has a $3.5 billion pandemic-busting plan that will kickstart and coordinate this work.

Compared with the trillions lost to COVID-19, at $3.5 billion, this plan is not only value for money; it’s exactly what the world needs to ensure that our children never again face the hardship and loss we’ve had to endure from COVID-19,” concluded Dr. Hatchett’s blog post.

In the U.S., the government has been focused on preparing for an influenza pandemic for years.

The U.S. CDC says the annual 'flu shot' does not prevent zoonotic influenza infections in humans.

Pandemic influenzas are novel contagious respiratory diseases past between people in which the severity is unpredictable because human immune systems have not established natural defenses.

The most recent influenza pandemic occurred in 2009, which caused up to 400,000 deaths globally, with about 12,000 people in the U.S.

And during 2022, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service has already confirmed avian influenza in ‘birds’ in various states.

However, in China, human cases of avian influenza A(H5N6) and related fatalities have been reported by Mainland health authorities in 2022.

The U.S. government is focused on these threats.

Recently, the U.S. National Influenza Vaccine Modernization Strategy and the White House American Pandemic Preparedness Plan outlined their priorities.

And the CDC's Influenza Risk Assessment report was recently issued in Dec. 2021.

Furthermore, on Feb. 25, 2022, the U.S.’s BARDA requested that Seqirus provide pandemic influenza vaccines (AUDENZ) and adjuvants for pre-pandemic stockpiling or for manufacture to support rapid response to an influenza pandemic or other public health emergency.

PrecisionVaccinations publishes fact-checked research-based antibody, antiviral, and vaccine development news.

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee