Malaria Disease Found to be a Late Arrival

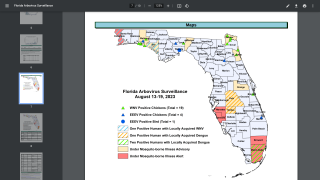

Studies have shown that many Americans do not take adequate health precautions before traveling to countries where infectious diseases are endemic.

And the consequences can be serious.

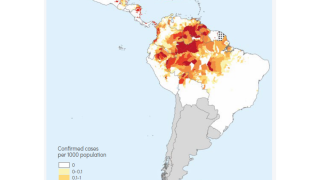

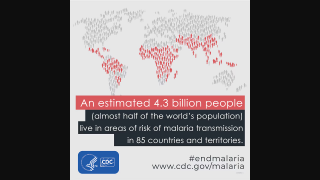

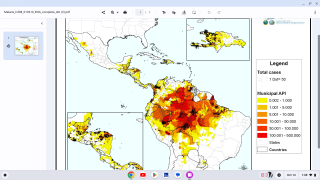

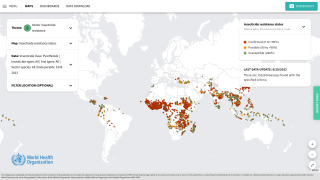

Travelers face various threats from mosquito-borne diseases, such as malaria.

In 2016, the estimated number of malaria cases reached 216 million, an increase of 5 million cases over 2015. Deaths stood at 445 000 in 2016, reports the WHO.

About 1,700 cases of malaria are diagnosed in the United States each year.

In a retrospective, observational study, travelers to Ethiopia were tracked for 11 years.

Of the 252 travelers included in this small study, 24.6% developed malaria, most caused by P. vivax.

87.1% of these cases were considered as ‘Late Malaria’, caused by P. vivax.

Late-onset malaria can often occur when hypnozoites, malaria parasites lying dormant in the liver, are reactivated.

“In prospective malaria chemoprophylaxis studies to date, follow-up has usually been limited to 1-month post-exposure and in the absence of a prolonged follow-up period, all late infections of P. vivax and P. ovale malaria will be missed,” the researchers wrote.

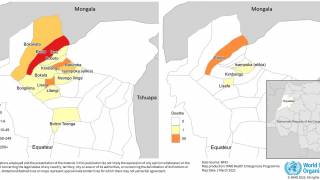

Recently, the world’s first malaria vaccine was rolled out in pilot projects by the World Health Organization (WHO). This vaccine, known as RTS,S, acts against P. falciparum, the most deadly malaria parasite globally.

RTS,S also known as Mosquirix, is the first malaria vaccine to successfully complete Phase 3 testing.

Since RTS,S is only partially effective, it will be essential that any vaccinated patients with a fever be tested for malaria. And those patients with a confirmed malaria diagnosis are treated with high quality, antimalarial medicines, such as Primaquine, says the WHO.

“The pilot deployment of this first-generation vaccine marks a milestone in the fight against malaria,” said Dr. Pedro Alonso, Director of the WHO Global Malaria Programme

“These pilot projects will provide the evidence we need from real-life settings to make informed decisions on whether to deploy the vaccine on a wide scale.”

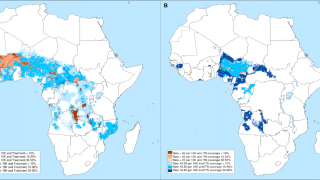

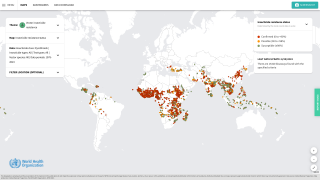

Malaria is caused by parasites that are transmitted to people through the bites of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes. P. falciparum is the most prevalent malaria parasite in Africa and responsible for most malaria deaths globally. P. vivax is the dominant parasite outside of sub-Saharan Africa, says the WHO.

How to treat a patient with malaria depends on:

- The type (species) of the infecting parasite

- The area where the infection was acquired and its drug-resistance status

- The clinical status of the patient

- Any accompanying illness or condition

- Pregnancy

- Drug allergies, or other medications taken by the patient

If malaria prevention medicines will be needed for the traveler, the Malaria Information by Country Table lists the CDC-recommended options. For many destinations, there are multiple options available.

Most drugs used in treatment are active against the parasite forms in the blood (the form that causes disease) and include:

- chloroquine

- atovaquone-proguanil (Malarone®)

- artemether-lumefantrine (Coartem®)

- mefloquine (Lariam®)

- quinine

- quinidine

- doxycycline (used in combination with quinine)

- clindamycin (used in combination with quinine)

- artesunate (not licensed for use in the United States, but available through the CDC malaria hotline)

In addition, primaquine is active against the dormant parasite liver forms (hypnozoites) and prevents relapses. Primaquine should not be taken by pregnant women or by people who are deficient in G6PD (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase). Patients should not take primaquine until a screening test has excluded G6PD deficiency, says the CDC

Most travelers are often surprised to learn that recent travel to a place where malaria transmission occurs is an exclusion criterion for blood donation.

Research disclosures: The authors report no relevant financial conflicts of interest.

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee