Flu Shots Turn Cold Cancer Tumors Hot

Chicago’s Rush University Medical Center researchers say they ‘have found that injecting cancer tumors with influenza vaccines turns "cold" tumors to "hot,", which is a discovery that could lead to an immunotherapy to treat cancer.

This innovative study was published on December 30, 2019, proposes that antipathogen vaccines may be utilized for both infection prevention and repurposing as a cancer immunotherapy.

The majority of patients have tumors that are “cold” — that is, the tumors don’t contain many immune cells, or they have cells that suppress the ability of the immune system to fight them, said these researchers in a related press release on January 7, 2020.

Increasing immune cells within a tumor can change it from “cold” to “hot” — more recognizable to the immune system. Hot tumors show higher rates of response to treatment, and patients with such tumors have improved survival rates.

Currently, some immunotherapies utilize live pathogens (disease-causing organisms) as cancer treatments, but these treatments only have shown lasting effects in a limited number of patients and cancer types.

“We wanted to understand how our strong immune responses against pathogens like influenza and their components could improve our much weaker immune response against some tumors,” said Andrew Zloza, M.D., Ph.D., assistant professor in Rush Medical College’s Department of Internal Medicine and senior author of the study.

Drawing on a National Cancer Institute database, researchers found that people who had lung cancer and hospitalization for a lung infection from influenza at the same time lived longer than those who had lung cancer with no influenza.

They found a similar outcome in mice with tumors and influenza infection in the lung.

“However, there are many factors we do not understand about live infections, and this effect does not repeat in tumors where influenza infections do not naturally occur, like skin,” Dr. Zloza said.

To find an alternative to the limitations of live infection, researchers inactivated the influenza virus, essentially creating a flu vaccine.

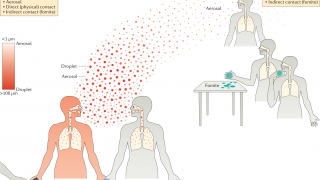

They found that direct injection of this vaccine into the skin melanoma of the mice resulted in the tumors either growing slower or shrinking. The injection made the tumor hot by increasing the proportion of a type of immune-stimulating cells (called dendritic cells) in the tumor, leading to an increase in a type of cells known as CD8+ T cells, which recognize and kill tumor cells.

Importantly, injecting a skin melanoma tumor on one side of the body not only resulted in the reduced growth of that tumor, but also in reduced growth of a second skin tumor on the other side of the same mouse that was not injected.

The study authors note that they observed similar systemic outcomes in a mouse model of metastatic triple-negative breast cancer, in which both primary tumor growth and the natural spread of the breast tumor to the lungs were reduced after injection only into the primary tumor.

“Based on this result, we hope that in patients, injecting one tumor with an influenza vaccine will lead to immune responses in their other tumors as well.”

“Our successes with a flu vaccine that we created made us wonder if seasonal flu vaccines that are already FDA-approved could be repurposed as treatments for cancer.”

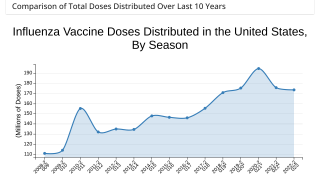

“Since these have been used in millions of people and have already been shown to be safe, we thought using flu shots to treat cancer could be brought to patients quickly,” said Dr. Zloza.

The researchers found that injection of such flu shots also resulted in a reduction of tumor growth.

To determine if similar results could be obtained with tumors from patients, the researchers developed a mouse model, which they call AIR-PDX.

To create this model, they implant a piece of the tumor and immune cells from a patient with cancer into a mouse that does not have a functioning immune system of its own – which prevents the mouse from rejecting the implanted cells.

The researchers used a patient’s lung tumor and melanoma metastasis in AIR-PDX models. They found that putting the flu shot in these patient-derived tumors causes them to shrink, while untreated tumors continued to grow.

Since new treatments are often compared to or combined with current frontline therapies for cancer, the researchers used immune checkpoint inhibitors in their studies. Immune checkpoint inhibition “releases the brakes” on immune cells so that they can fight the tumor.

The researchers found that flu vaccines can reduce tumor growth when used alone, whether or not the tumor is responsive to checkpoint inhibitor therapy. When they combined the flu vaccine with a checkpoint inhibitor together, an even greater reduction in tumor growth occurred.

“These results propose that eventually, both patients who respond and who do not respond to other immunotherapies might benefit from the injection of influenza vaccines into the tumor, and it may increase the small proportion of patients that are now long-term responders to immunotherapies.”

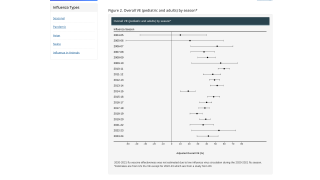

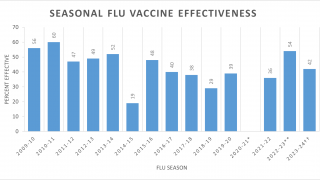

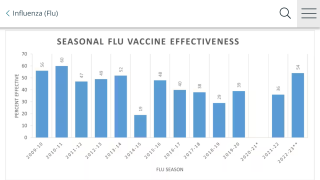

Five different influenza shots for the 2017-2018 flu season were used in this research.

But, only 4 were effective in achieving the same results in fighting tumors.

One flu shot with a synthetic adjuvant (an immune modifier) had no antitumor effect and maintained other cells (called regulatory B cells or Bregs) that suppress an immune response.

When the adjuvant was removed from the vaccine, it became effective. Similarly, when the B cells were removed, the vaccine also then became effective.

That all 5 vaccines provided protection from flu infection, but one was ineffective in reducing tumor growth “demonstrates a disconnect between the principals of immune responses needed to fight pathogens versus tumors,” Dr. Zloza said.

“It also highlights the need for additional consideration regarding what adjuvants are included in immunotherapies and which vaccines could be used to treat cancer.”

“Since humans and mice are about 95% genetically identical, the hope is that this approach will work in patients. The next step planned is to conduct clinical trials to test various factors.”

“Although we are currently studying the use of other vaccines as well, the seasonal flu shot is safe and recommended for most people over 6 months of age, including most patients with cancer.”

“This is why we chose to start with it.

“The flu shot is inexpensive and it has a quick translatability since it is an FDA-approved drug that we are repurposing,” Zloza continued.

Jochen Reiser, M.D., Ph.D., a professor at Rush Medical College is a co-author of the study.

No conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Cancer vaccine news published by Precision Vaccinations.

Our Trust Standards: Medical Advisory Committee